The Wandering Archaeologist

by Letizia Triches

This story began a very long time ago at a sun-drenched sea-bathed Cuma, today a small town in the Phlegrean Fields, but once the most important city to be founded in Campania by the colonists from Chalcedon. In an even more remote epoch, one of the poets wrote that at the end of his flight Daedalus had landed on the citadel of Cuma to erect thereon a temple sacred to Apollo. On the gilded gates of the temple there remained engraved the effigy of Daedalus grieving for the fall of Icarus who had disappeared as a huge purple-coloured angel into the waves of a dark sea.

Most ancient landing-place of Aegean navigators, Cuma as early as the eighth century before Christ had given welcome to the Chalcedonians from the island of Euboea, who transformed it into the farthest outpost of the Greek colonies in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Then the Samnites swept over the Chalcedonians, who although being annihilated, still managed to hand down the invaluable signs of their alphabet, together with their advanced civilised life-style.

Last century there arrived on the scene some clandestine diggers, who despite considerable adversity managed to overcome the terror of the place, which at that time was no more than a desolate swampy land exuding fumes of malarial fever.

Gold objects, bronzes and painted vases were all within easy reach under a thin covering of earth, treasures waiting to be slipped among their greedy fingers.

Yet it was another type of treasure that was sought for by Ambrosino the archaeologist, who also appeared here some thirty years ago. To be exact he was more of a geologist than archaeologist, yet he breathed the atmosphere of archaeology, and it is not far from the truth to say that deep down he was an archaeologist, though of a very rare breed, beyond the normal range. Rather than in search of treasures from the earth, he probably scoured the landing-stage area that was Cuma for a deeper sense of freedom and creative truth, which by then he was arriving at by pure intuition, and which represented for him the only possible relationship with the outside world, since only within a dimension of such fantasy could he find its justification.

Yet it was another type of treasure that was sought for by Ambrosino the archaeologist, who also appeared here some thirty years ago. To be exact he was more of a geologist than archaeologist, yet he breathed the atmosphere of archaeology, and it is not far from the truth to say that deep down he was an archaeologist, though of a very rare breed, beyond the normal range. Rather than in search of treasures from the earth, he probably scoured the landing-stage area that was Cuma for a deeper sense of freedom and creative truth, which by then he was arriving at by pure intuition, and which represented for him the only possible relationship with the outside world, since only within a dimension of such fantasy could he find its justification.

The year of his decision was 1965, and if today, now that some time has passed, we wish to extract its spiritual significance, we must examine the particular psychological relationship he had developed with the ancient past. Beyond the veil of fascination and attraction of coast-line Hellenism, Ambrosino wanted to penetrate into the wild authentic world of a more provincial culture, to become the magic archaeologist of a native folklore world that has never ceased to exist.

Near the lead-coloured waters of Lake Avernus, which had accumulated in the volcano’s crater, to remain there ever unperturbed, the Mount of Cuma had been further developed, now full of long underground passages, riddled with criss-crossing walks extending in every direction like a gigantic ant-hill.

For his extraordinary ability to listen to the past as if it were the present, Ambrosino was still able to recall the name of the person who had then first begun that patient work of persevering excavation more than a thousand years earlier, being the name of an ingenious military architect of the Emperor Augustus, who had joined Cuma to Port Julius of Lake Avernus by means of a very long tunnel.

The Byzantines of Narses had settled there, while the Goths lay siege, hidden away on the mountain-side. In the medieval period the inhabitants of the place continued there by transforming it into a castle. By now the temple of Apollo had long since become a Christian basilica. Then later the pirates made it their hide-out. In time the mount had become a stone quarry, whose grottos were often used also as stables and storage cellars in a continuous alternating between re-stocking and refurbishing.

How was it now possible for Ambrosino the archaeologist to recognise from these wounds, which the resigned earth shamelessly revealed before his eyes any real evidence of an ancient presence of a past culture? In his spiritual journeyings he continued to remember as he looked back in retrospect. Perhaps another adventure might have been repeated for him, like the one that befell a forerunner of his who one day, a little before Ambrosino was born, happened to note in a cell, no different from the others, a far too precise cut which could not have been made by chance. On following up this incision he arrived at a trapezoidal opening, closed in by a tottering wall. Behind this wall lay a long large-scale dromos. The corridor led to a sombre grotto, with a large-niched vault, which was nothing less than the Sibyl’s cave.

How was it now possible for Ambrosino the archaeologist to recognise from these wounds, which the resigned earth shamelessly revealed before his eyes any real evidence of an ancient presence of a past culture? In his spiritual journeyings he continued to remember as he looked back in retrospect. Perhaps another adventure might have been repeated for him, like the one that befell a forerunner of his who one day, a little before Ambrosino was born, happened to note in a cell, no different from the others, a far too precise cut which could not have been made by chance. On following up this incision he arrived at a trapezoidal opening, closed in by a tottering wall. Behind this wall lay a long large-scale dromos. The corridor led to a sombre grotto, with a large-niched vault, which was nothing less than the Sibyl’s cave.

There exist ten Sibyls in number, the Cumaean one being the eighth. On inhaling an intoxicating gas, the sibyl would give vent to vague inarticulate sounds which gave life to her response, and a certain priest interpreted it.

Virgil recounts that before descending to the lower world- access to Hades was situated not very far from the cave near Lake Avernus-Aeneas consulted the Sibyl. But only much later, when Rome was drawing near to the end of its age of kings, was king Tarquin able to acquire from the Sibyl the Sibylline books, enigmatic writings and texts sacred to the Roman state. Mindful of this episode Ambrosino, thought of the Sixth Book of the Aeneid and the entrance to the cave and he imagined he could see the sibyl, who “horrendas canit ambages antroque remugit”.

From that time another wanderer journey opened up for him. From then on Ambrosino the painter was to change his travels within art and through art, even his own writings in paint would be charged with prophetic meaning to follow his journey right down to our present day. And these are days, these more recent ones, in which he has yet again initiated a kind of archaeological digging but this time beyond the epidermis itself-that is, the thin protective layer of the painting’s skin, to look beyond, without dwelling on the threshold of the surface he has painted.

Ambrosino’s artistic output in 1994 has become ever more intensive and increasingly rapid. They are works wherein disintegration of the painting’s skin has come about, as if it wanted to present itself as the shadow of a masterpiece come down to us from an ancient past, as indeed the title of many of his works suggest: Icon, for example. Of these masterpieces from the past we would like to unveil the transparent image of their primitive appearance, but we become immediately aware of our inability to have at our disposal any practical means for restoration, as it would be impossible in our imaginations to reproduce any clear-cut evidence for primitive figures, except partially.

The quality of the painting is however, now proposed by these neutral nebulous chromes no less, into which colour zones are separated off; rare are those brilliant whites, real and true visual referents vaguely suggesting gestures and physical features. A few shreds of colour, precious like lapis-lazuli or scarce ones such as amethyst remain in suspension on a thickness that appears to be made up of crusts, of mould and powder mixed with glue, wax and fibre-glass. Above and between the interstices of this colour a sign, which is almost irreverent for its autonomy, is hinted at. The sign is like a darting flash, a little restless, at times sparkling, but always a bright component, trying to associate itself with images varying between a visionary configuration and an organic abstraction. At this point any reconstruction one may have assumed of the original masterpiece can only be subjective, having almost archaeological overtones and coming about in our sub-consciences. Any possible error in interpretation thus becomes privilege of those who read the work. Ambrosino does realise in fact that communication must undergo continuous development to ensure survival. The moment has arrived in which he must try to put together a synthesis that can contain all the various expressions of one single recognisable concept, which he has long held in his itinerary as artist, namely, the concept of the sacred.

The quality of the painting is however, now proposed by these neutral nebulous chromes no less, into which colour zones are separated off; rare are those brilliant whites, real and true visual referents vaguely suggesting gestures and physical features. A few shreds of colour, precious like lapis-lazuli or scarce ones such as amethyst remain in suspension on a thickness that appears to be made up of crusts, of mould and powder mixed with glue, wax and fibre-glass. Above and between the interstices of this colour a sign, which is almost irreverent for its autonomy, is hinted at. The sign is like a darting flash, a little restless, at times sparkling, but always a bright component, trying to associate itself with images varying between a visionary configuration and an organic abstraction. At this point any reconstruction one may have assumed of the original masterpiece can only be subjective, having almost archaeological overtones and coming about in our sub-consciences. Any possible error in interpretation thus becomes privilege of those who read the work. Ambrosino does realise in fact that communication must undergo continuous development to ensure survival. The moment has arrived in which he must try to put together a synthesis that can contain all the various expressions of one single recognisable concept, which he has long held in his itinerary as artist, namely, the concept of the sacred.

Since we can gain cognition of this through our sense of sight it is necessary for him to relate idealistic metaphysical entities, associated with the same concept of the sacred, back to a powerfully meaningful image. Such entities should thus be countermarked by exact elements that permit their immediate recognition. But his current work of “excavation”, beyond the skin surface of the painting, does not grant him the opportunity to do so, and as a consequence the question arises for the artist as to what the essential elements are, which are to continue unchanged as to allow the configuration to remain ever subject to interpretation, despite all else.

The answer most likely comes to him from the open panoramic view that greets him across the terrace of his studio, which opens up over the wide stretches of the sea.

Greek and Roman cultures, ancient native cultures and contributions made by oriental civilisations and, above all, the Christian sense of religion. A culture which has formed itself within a certain geographic area, heir to an earlier culture that flourished within the same space. How far do they both permeate? To the point where everything can unite in the Mediterranean’s vast memory, may be the answer.

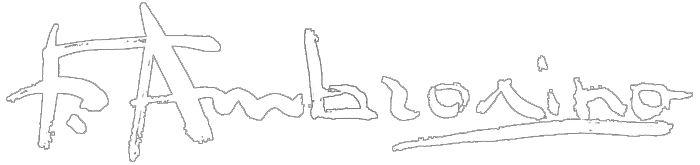

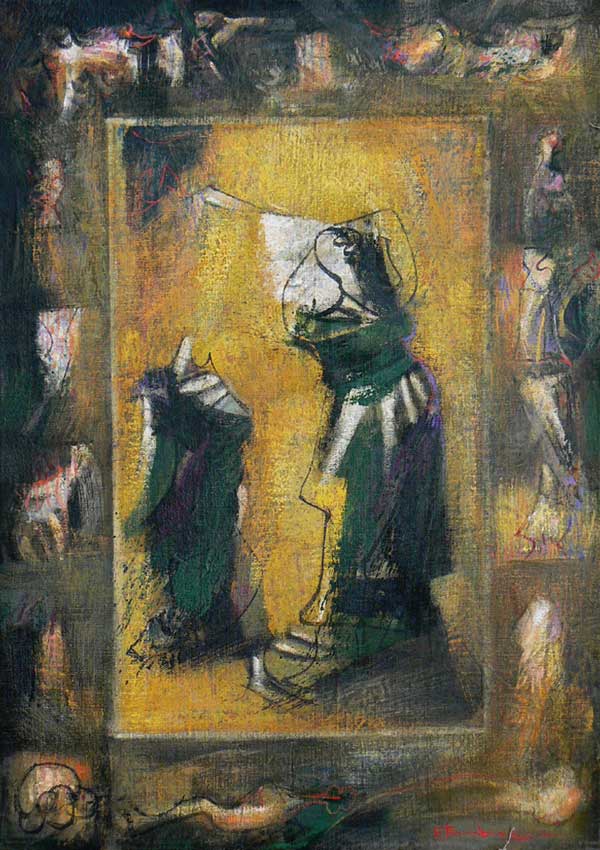

In many recent works his composition materials make use of a kind of frame made up of a certain number of squares painted on the same surface, each containing a different “episode”. The purpose of the frame is, as a rule, to demarcate, and, at the same time to pinpoint a central area. In these works the converse takes place. It is the centre that refers back to the frame, where in fact the story takes place. But what story? That of a hypothetical Via Crucis? I would say not, as here the story is set in a spiritual and not a narrative dimension. The task of this hypothetical frame is therefore, to indicate a fragment without, however, establishing any precise sequence, without a fixed order telling us which part we have to begin with to be able to distinguish and trace back the working of the artist. Everything turns out to be ruled by imagination alone. Other panel squares need not possess very well-defined demarcations but may allow other situations to come about, but whether these are past or still to come with respect to one’s own ideas is still unknown.

In many recent works his composition materials make use of a kind of frame made up of a certain number of squares painted on the same surface, each containing a different “episode”. The purpose of the frame is, as a rule, to demarcate, and, at the same time to pinpoint a central area. In these works the converse takes place. It is the centre that refers back to the frame, where in fact the story takes place. But what story? That of a hypothetical Via Crucis? I would say not, as here the story is set in a spiritual and not a narrative dimension. The task of this hypothetical frame is therefore, to indicate a fragment without, however, establishing any precise sequence, without a fixed order telling us which part we have to begin with to be able to distinguish and trace back the working of the artist. Everything turns out to be ruled by imagination alone. Other panel squares need not possess very well-defined demarcations but may allow other situations to come about, but whether these are past or still to come with respect to one’s own ideas is still unknown.

Completed fragments, individual, separate and yet in layers. The need for setting everything within a frame brings it about that even in the “chess-board ” works we are still able to recognise a kind of centre, a focus point which gives an impulse for the creation of other figures in the more peripheral areas. There are no individual miracles, but rather the sense of miracle, and just as happens for those who sing of the beliefs of the peoples, so the painter now has the outstanding capacity to make things become objective. The frame is the real objective of the picture, playing the role of sign, while the centre of the painted centre becomes a mirage of pure meditation, an area of a meaningful illusion. We eventually realise that there is no real and true objective in his knowledge, since the point of reference which our visual perception leads us to, crumbles away no sooner we try to embark on a more accurate process of identification. The composition scheme of some pictures, by analogy, leads us to presuppose a system of Christian symbols. But it is here that the “figures” – nothing other than suggestions of movement generated by a build-up of colours in which the black sign describes further reasons for interpretive reading- retreat totally from that interpretation which we had ascribed to it in the first place. Thus we cannot obtain any kind of verification, but can only form a simple impression.

The painting is a “Transfiguration” in which an opaque almond of milky light is flanked laterally by two ambiguous presences associated with an idea of flight, almost gushing out from the outline of a mountain, on which lie various encrustations of colour pinned down and perhaps transformed into body. It is only its shape now become mobile and slender that might suggest such a significance, since in contrast, there is no exchange of signs to grant a traditional process of communication. One’s vision wavers and the image fluctuates, now completely detached from its historic context. Its definite meanings are fixed, as it were, to the threshold of our eyes, and what remains is only the emptiness of a word that in the presence of a similar picture may only be described as needing to be transformed into a “non-silent film”.