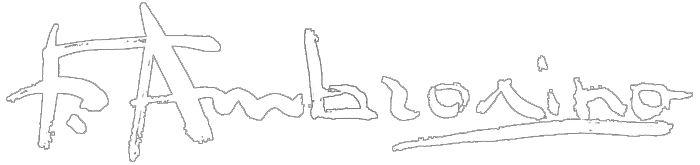

The Icon as Iconography

by Barbara Rose

And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revelers in the blood bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.

Edgar Allan Poe, The Masque of the Red Death

Ferdinando Ambrosino began as a painter of landscapes, only to become a painter of icons. How and why did such a radical transformation, which suggests more than ordinary stylistic evolution, take place? Such a dramatic change of subject, content and form suggests an event of major significance,a psychological awakening brought on by nothing less than a spiritual epiphany or an emotional trauma.

Ferdinando Ambrosino began as a painter of landscapes, only to become a painter of icons. How and why did such a radical transformation, which suggests more than ordinary stylistic evolution, take place? Such a dramatic change of subject, content and form suggests an event of major significance,a psychological awakening brought on by nothing less than a spiritual epiphany or an emotional trauma.

In Ambrosino’s case, his decision to abandon a pleasing style of cheerful, abstract landscapes based on Impressionist precedent appears to have been triggered by the sudden vision of the meaning of the catastrophic events of our century.

Already in the early years of the twentieth century, the Spanish philosopher Miguel prophetically defined modem historical consciousness as “el sentimiento tragico de la vida.”

This existential tragic sense of life is common to those who think and feel deeply in any given time, but the events of our own epoch have heightened our degree of consciousness to a new and painful awareness, which eventually became the content of Ambrosino’s paintings. In this connection it is significant that Ambrosino was born on the eve of World War II in Bacoli outside of Naples and that he was trained as a geologist. His knowledge of geology surely sensitized him to the idea of the metaphor of strata of experience, layers of buried history, to be excavated for their meaning.

That the artist was born in the shadow of the major ancient archaeological site of Cuma is also significant in relation to the imagery he ultimately developed to express his sense of history. In antiquity, the area near Bacoli that is now an archaeological park was famed and feared as the home of that most redoubtable prophetess, the Cumaean Sybil.

According to Virgil, the entrance to the gates of hell was near the cave where Aeneas consulted the Sybil. In the sixth book of Aeneid, the Sybil appears to the founder of Rome. Later, King Tarquin acquired the sibylline books sacred to the Roman State. In the shadows of the caves of Cuma the Greeks consulted the divine oracle who was the medium of transmission of the messages of the gods. There, the mysterious and terrifying Sybil inhaled hallucinogenic gas and in a trance responded to questions the priest interpreted.

The subterranean caves are near Lake Avernus where water accumulated near the volcano’s crater.

In a spot as rich in historical memory as the en virons of Cuma, dark shades and phantoms of history are sure to hide. Originally, Cuma was a village in the Campi Flegrei, now it is an archaeological park where ghosts of the past and fragments of history interact with nature.

Cuma was founded by Greek colonists from Chalcedon who believed that winged Daedalus landed there and built a temple to Apollo. Christians transformed the temple of Apollo into a basilica where Christ was worshiped. In ancient times, the mound of Cuma, now crossed by labyrinthine underground passages, were excavated by the military architects of the Emperor Augustus. He originally joined Cuma to Port Julius of Lake Avernus through a tunnel. The Byzantines of Narses eventually conquered the area, which in turn was besieged by the Goths from the North who built a castle to defend their conquest.

Cuma was founded by Greek colonists from Chalcedon who believed that winged Daedalus landed there and built a temple to Apollo. Christians transformed the temple of Apollo into a basilica where Christ was worshiped. In ancient times, the mound of Cuma, now crossed by labyrinthine underground passages, were excavated by the military architects of the Emperor Augustus. He originally joined Cuma to Port Julius of Lake Avernus through a tunnel. The Byzantines of Narses eventually conquered the area, which in turn was besieged by the Goths from the North who built a castle to defend their conquest.

The historic strata of such a place thus become part of a collective memory of bloody conquest and resurrection.

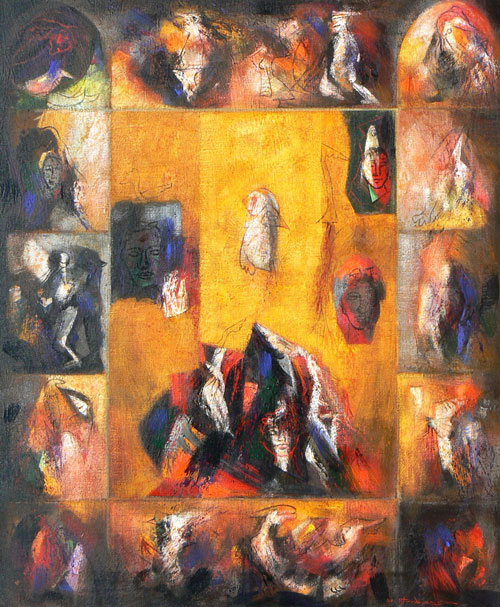

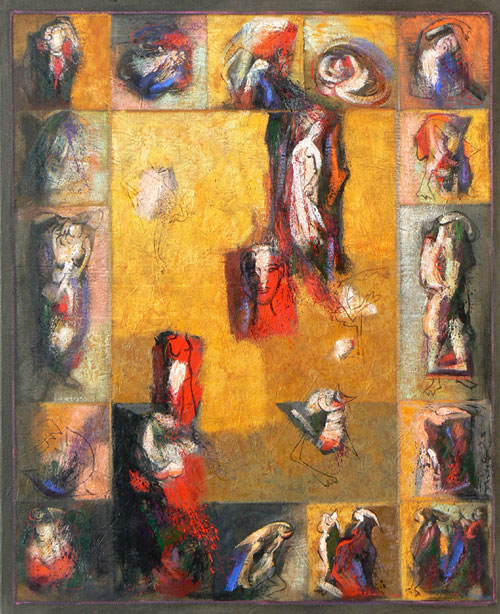

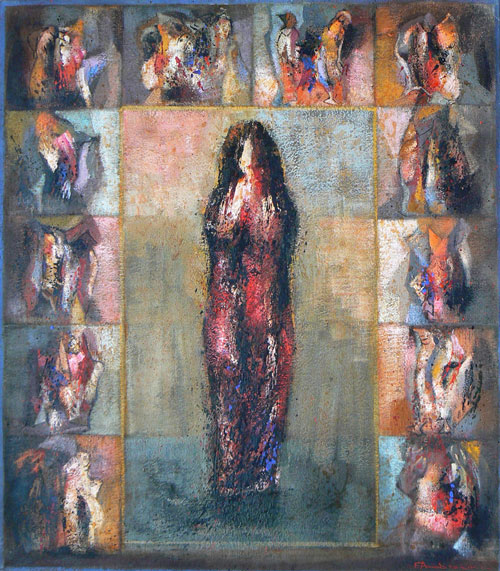

The labyrinth caverns at Cuma are dark and shadowed; surely they must prefigure the compartmentalized “icons” that Ambrosino began to paint at the beginning of the nineties. Housed in the shadowy recesses of Ambrosino’s icons which recall the dark secrets of Cuma, figures twist and turn, faces appear and disappear in the dark mists of a dream.

The stylized drapery that shrouds the figures have an ambiguity further confused in the shadowy recesses of memory, where thoughts struggle to become conscious, only to remain half formed, then to dissolve back into the darkness of the unconscious.

The allusions, however, are not to any specific autobiographical memories, rather they are hints of collective memory. The vignettes, housed within the cell-like compartments, each tell a different but similar story. They allude to narratives of conflicts, struggles and martyrdom taking place in the secrecy of decaying niches that remind us of the underground caverns of Fellini’s Satyricon in which the decadence of the last days of the Roman empire are subliminally substituted for those of the decadence of the post War dolce vita, which had its ultimate manifestation in the darkest depravity of the crimes of corruption of the succeeding decades characterized by the worst scandals of the “tangentopoli” and its orgiastic modus vivendi.

Not the private realm of specific trauma, but the collective tribulations of the race are commemorated in the shadows of the caves of Cuma, where the Sybil prophesied dark events to come. This idea of a connection, a door, or an entrance to a netherworld in Ambrosino’s paintings becomes a, metaphor for access to the unconscious and the world of dreams.

Known as the oldest and most important destination of the Aegean navigators, Cuma was discovered in the eighth century B.C. by the Chalcedonians from the island of Eubea. There they founded the farthest outpost of the Greek colonies in the Tyrrhenian Sea, leaving their alphabet and other advances. Cuma, thus was from the first associated with empire and fall of empire. The story of the rise and fall of successive civilization chronicled by such historians as, Giordano Bruno, Gibbons, and Toynbee include the transformations undergone by Cuma, which was in turn used as a stone quarry, a pirate retreat, and storage depot. Its cell-like labyrinthine compartments were from their origin associated with fundamental myths of iman’s creativity, his daring and his hubris. We know, for example, that the gilded temple at Cuma was decorated with the image of Daedalus mourning the fall of his son Icarus.

Ambrosino’s early work was noted for his interest in large scale grandiose themes.

In the early sixties, he painted large, neo-realist paintings based on the theme of the struggles of the proletariat.

In 1965, a visit to the cave of the Cumaean Sybil was a turning point. Although he does not say so directly, apparently there he had a vision that slowly began to take shape in his painting. Certainly he knew that part of the story of Cuma concerned the origin of human creativity itself, since it is thought that this was the site where Daedalus fashioned the wings that permitted him to ascend to the heavens, but in the hands of his son Icarus become the emblem of hubris.

The finding of his vocation as an artist is not dissimilar to that of the Stephen Daedalus, the hero of James Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist, who dedicates himself to the tradition of writing, addressing his ancestor “old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.

By the time Ambrosino had his first person show in 1967, the muscular figures of his early work had given way to lyrical landscapes that became increasingly abstract. By the mid seventies, his work had a mature sophistication and a group of fifty paintings were sent on tour in Greece, Turkey, Rumania and the Soviet Union. These colourful, expressive paintings, full of light and motion, had considerable success.

In 1977, the artist made a group of ceramic sculptures in terracotta that brought his attention back to the human figure. But, essentially, he remained a landscape painter.

Towards the end of the eighties, however, the landscapes became darker and more turbulent. Despite their debt to Cubism and abstract expressionism, these works were still clearly tied to nature.

In 1990, we find the human figure once again appearing in Ambrosino’s works, but here the form is clearly in conflict with its context, seeming to be struggling for some kind of liberation from what appears to be the confinement of the picture plane and the rectangle. Instead of the stillness of the icon, we have writhing movement, a seeming contradiction of the iconic format and its dedication to stasis and symmetry; symmetry becomes asymmetry, the conventions of east and west are hybridized.

In 1990, we find the human figure once again appearing in Ambrosino’s works, but here the form is clearly in conflict with its context, seeming to be struggling for some kind of liberation from what appears to be the confinement of the picture plane and the rectangle. Instead of the stillness of the icon, we have writhing movement, a seeming contradiction of the iconic format and its dedication to stasis and symmetry; symmetry becomes asymmetry, the conventions of east and west are hybridized.

The unquiet, uneasy figures suggest the desperation of Michelangelo’s bound slaves struggling to escape their bindings, to burst forth from the block of stone that confines them to earth and mortality. Like Michelangelo’s slaves, Ambrosino’s figures suggest the human energy of expansion and search for an elusive freedom, the wish for which is hubris itself.

Ambrosino’s contemporary adaptation of the structure of the Russian icon to the purposes of an expressionist modem art raise questions concerning style, intention and technique that are relevant within the context of postmodernism hybridization and appropriation. However, unlike media based postmodernism, Ambrosino’s painterly painting makes a case not for reproduction but for the sensual tactile qualities of the painterly original. In this, he consciously adheres to the Western tradition as established in the Renaissance and not to earlier archaic styles. Moreover, although there is reference to collective archetypes, each of the intertwined figures and faces are individualized-another distinctly Western characteristic.

Drawing is essential to a pictographic sense and Ambrosino’s ability to rapidly delineate with a quick skipping fine line the notations that suggest figures in motion became an important consideration.

The typology of the figures recalls Henry Moore’s drawings, which in turn inspired Jackson Pollock to create a kind of picture-writing that dematerialized bodies into pictographic symbols. Picture-writing, of course, is common to preliterate archaic cultures not yet capable of communicating imprint. The sense of condensed narrative is preserved in Ambrosino’s iconic compartments, which suggest scenes of terror and mystery, relating his vision to Delacroix’s perfumed orientalizing style. Even the palette recalls the intense colour contrasts and dramatic violence of swooning figures expiring in the Death of Sardanapalus.

Like Delacroix, Ambrosino appreciates the luxury and lushness of curving sinuous forms and glowing painterly surfaces. In this orientalizing tendency, his work recalls the jewel tones and sfumato of the Symbolist paintings of Delacroix’s heir Gustave Moreau, who transferred this late nineteenth century love of luxe claime and volupté to his most famous student, Henri Matisse. Byzantine art deformed and distorted the realistic space and scale of classical painting in a way that anticipates the compressed expressionism of modern art.

In 1993, Ambrosino’s figurative imagery began to take the specific form of icons. The compartments became clearer; their contents ever more spectral. Ghostly apparitions, indistinct and mysterious, flowed in and out of evanescent smoky space. Although not nameable or distinct, they suggested scenes, vignettes and narratives, like those found on the predellas of altarpieces or the panels of bridal cassone paintings.

In 1993, Ambrosino’s figurative imagery began to take the specific form of icons. The compartments became clearer; their contents ever more spectral. Ghostly apparitions, indistinct and mysterious, flowed in and out of evanescent smoky space. Although not nameable or distinct, they suggested scenes, vignettes and narratives, like those found on the predellas of altarpieces or the panels of bridal cassone paintings.

Confronted by ambiguity, the viewer must supply the narrative of warriors and saints, combats on horseback, the historic battles of cavaliers and crusaders.

The possibility of indicating monumental space in the format of the icon is intriguing. The problem of figuration is, of course, a central feature of modem art once it attempts to free itself from the conventions of representation

One solution to the spatial dilemma is to depict inside the frame in scenic vignettes. The compartments also speak of memories of the structure of Sistine Chapel. But what we see are not the scenes of the Old Testament, but tumbling forms and falling angels of the Last Judgment.

The painterliness of an expressionist style is heightened by the use of scumbling. Fragments of anatomy seem to suggest dismemberment; hands and feet, the tortured pain of medieval trumeau, the gothic arches, flames and glories, aureoles and night light pioneered by the pre-Caravaggists Moretto and Savoldo in the north of Italy.

Everything points to the conclusion that Ambrosino’s subject is man’s fate. The conception of history as a painful and repetitious narrative contradicts the iconostasis, which represents the immobility of the static and the timeless, which is outside of history consciousness

Ambrosino replaces the iconostasis with the mobile and ever-changing modem sense of mutation transformation and struggle. This is necessary to be true to our time because struggle and tension is the essence of the dialectic. In these terms, then the painter’s job is to depict images in the process of assuming form while resisting dissolution. In the shadowy recesses, evanescent figures appear as veiled. They remind us of shrouded figures in Henry Moore’s drawings, which Jackson Pollock transformed into stenographic signs.

Pollock’s veiled image as he defined it hid often horrific and terrifying imagery. What is veiled is unnameable and unspeakable. In these “icons” depicting man’s fate, entangled humanity is seen in a variety of positions and gestures, both legible and illegible.

The fine line of brush drawing often suggests bones just as the darkness recalls the shadowy caverns of Piranesi’s Carceri. The sense of a suffocating imprisonment is that of Sartre’s Huis Clos from which there is no escape.

The figures are engaged in an erotic dance of death; their writhing suggests on the one hand, erotic engagement, and on the other, blazing funeral pyres, and bindings and chains of enslavement.

The figures are engaged in an erotic dance of death; their writhing suggests on the one hand, erotic engagement, and on the other, blazing funeral pyres, and bindings and chains of enslavement.

Ambrosino’s appropriation of of Russian icons presents the possibility of using the stylistic conventions of civilization to refute those of our own. Thus the iconic structure becomes a carrier of symbolic meaning as opposed to an occasion for sacred iconography.

The piety sincerity, and purity of the believing artisans who created these sacred objects of worship is implicitly contrasted with the decadence, cynicism and mondanity of our own time and its materialistic values. In the shadowy recesses of memory thoughts struggle to become conscious, only to remain half formed and dissolve.

Not the private realm of specific trauma but that of the human race itself surface and are seen in depth in painting. The brushed canvas is skin, but is penetrated by dark gothic arches and archaeological references. The works are full of various types of ambiguity, including palimpsests and pentimenti. Information provided and omitted universalizing character, non specific, yet we sense…echoes of lamentations and crucifixions.

The lava-like explosions that cause matter to spill out beyond the iconic confines recalls the volcanic eruptions typical of the area around Naples that identify the spot as a major geological shrine to earth’s destructive power and the potential for ecological catastrophe we feel more imminent day by day. In their recollection of the memory of earlier destruction, they are in themselves incarnations of prophecy that should be studied and heeded. Thus the icons are signs, indeed warning signs. They speak not of a stable and unchanging conception of the world, but of a fluid and fugitive reality that we must grasp to understand.

____________________________________________________________________________

Barbara Rose (born 1938) is an American art historian and art critic. She was educated at Smith College, Barnard College and Columbia University. She was married to artist Frank Stella between 1961 and 1969. In 1965 she published ABC Art in which she described the characteristics of minimal art.

Barbara Rose (born 1938) is an American art historian and art critic. She was educated at Smith College, Barnard College and Columbia University. She was married to artist Frank Stella between 1961 and 1969. In 1965 she published ABC Art in which she described the characteristics of minimal art.